1.1

Upper reaches of the Mann River.

Photograph: Grahame Webb and Charlie Ahnolis, 1988.

As we see from the long steep banks, the rivers of NE Arnhemland are ancient; so too is the ganma metaphor.

Yolngu people see a powerful metaphor in the meeting and mixing of two streams which flow-one from the land, the other from the sea-into a mangrove lagoon on Caledon Bay in NE Arnhemland. The theory of this confluence, called gaṉma, holds (in part) that the forces of the streams combine and lead to deeper understanding and truth.* It is an ancient metaphor, one which has served Yolngu people well in the past. In recent discussions among the Yolngu and those non-Aboriginal Australians they have chosen to work with them, gaṉma theory has been applied to the meeting of two cultures–Aboriginal and Western. Thus, we may use the term 'ganma' in English to refer to the situation where a river of water from the sea (Western knowledge) and a river of water from the land (Yolngu knowledge) engulf each other on flowing into a common lagoon and becoming one. In coming together, the Streams of water mix at the interface of the two currents, creating foam at the surface, so that the process of ganma is marked by lines of foam. In terms of the ganma metaphor, then, this book is part of the line of foam which marks the boundary of interchange between the current of Yolngu life and the current of Western life in contemporary Australia.

1.2

Glyde River, NE Arnhemland.

Aerial photograph: Donald Thompson, 1937.

The meeting of river and sea is the dominant landscape feature along the coast of Arnhemland. The dynamics of the meeting vary cyclically with tide and season. Metaphors of such meetings as we see pictured here are important in Yolngu cultural life.

In picturing the streams which constitute contemporary Australian life we are examining cultures that treat metaphor in different ways. We are dealing with different conceptual systems but also with different ways of using conceptual systems. European Australians assume that their language represents and signifies 'the world as it is'. They pay scant attention to questions of how meaning has been created, nor do they see such questions as related to their daily life. By contrast, among the Yolgnu, the cosmos is acknowledged as one whose meanings have been created and have a history embedded in the lives and social actions of 'Ancestral Beings' in the 'Dreamtime'. This meaning and history is sometimes referred to as 'song'. The explanation that Ancestral Beings created meaning in this world in their actions of social living is a necessary and inevitable component of every aspect of ordinary Yolgnu life. Yolngu people continue to sing the world into existence as an everyday activity. In the Western cosmos of the latter part of the 20th century, hints of a transcendental 'other' world rarely intrude. Religion as an institution is largely separated from everyday life in this secular society, even for religious people. But before the modern era, such was not the case for Western culture. Metaphors were taken very seriously indeed in the Christian Middle Ages. Nature was not simply like a book, rather nature actually was a book to be read, like the Bible, in order to discover God's purposes. There were 'books in the running brooks, sermons in stones'.

(W. Shakespeare, As You Like It, act II, scene I, line 12); nature was one great metaphor, full of hidden meanings and symbols, referent to another world, to other-worldly creatures and to the time of creation. This type of metaphor and symbology was common in Christianity as late as the 18th century (see Beasts and other illusions, pp. 1 - 11).

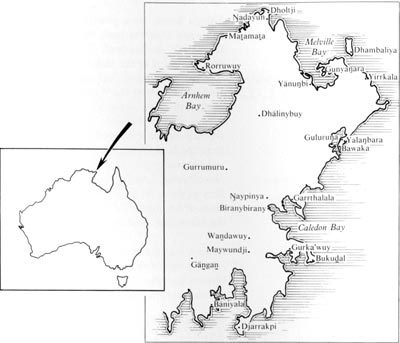

1.3

Small-scale map showing the location of Yolngu homeland centres in NE Arnhemland.

Yolngu people won back their land after the passage of the 1976 Northern Territory Land Rights legislation. Indeed, by challenging their dispossession in the High Court of Australia in 1970, the Yolngu people were instrumemtal in creating the climate which led to this legislation.