3.1

The partially submerged head of a crocodile may be perfectly camouflaged. The moment of recognition may produce terror in the European or respectful admiration in the Yolngu. Photograph: Patricia Caulfield.

Both Yolngu and European Australians frequently express incredulity at the way people of the other culture regard and respond to elements of the natural world. Crocodiles are one such element. On the one hand, European Australians are likely to find the love which Yolngu evince for crocodiles quite incomprehensible, and on the other hand, Yolngu find the fascinated revulsion which characterises European Australia's attitude to crocodiles quite unfathomable. In reality, perception of the crocodile in the two cultures is more varied and complicated than such a polarity can encompass. In this exhibit we look beneath the surface of these views to identify the cultural complexities which they reflect.

Two species of crocodile are to be found in the Laynhapuy: the estuarine salt-water crocodile (Crocodylu s poroms) and the smaller fresh-water crocodile (Crocodylus johnstom). The salt-water crocodile, which ranges from India through Australia to the Solomon Islands, is one of the largest and most powerful of all animals. It can live for over a hundred years. Humans who fail to respect this great creature in its own territory can find their lives threatened. Around the world, hundreds of people, perhaps thousands, are taken as crocodile prey each year. Yet, the number of Australians killed by the crocodile each year remains smaller than the number of Melbournians killed by the motor car each week.

Fish.

he listen.

He say

'Oh, somebody there.'

Him frightened,

too many Toyota.

Make me worry too.

Bill Neidjie (who lives in East Alligator River country, Arnhemland), in B. Neidjie, S. Davis & A. Fox, Kakadu man. Bill Neidjie, Mybrood, n.p., NSW, 1985, p.42

3.2

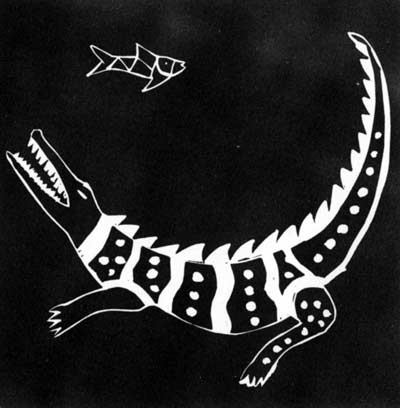

Bede Tungatalum, Bathurst Island, Crocodile and fish, woodcut.

The fish and crocodile are part of an ecological web which of course includes all humans that live in the same land. As a species, the fish has much more to fear from 4-wheel-drive vehicles (and the forces they represent) than from crocodiles.

EUROPEAN TEXTS ON CROCODILES

An ancient text

The river Nilus nourisheth the Crocodile: a venomous creature, roure fooled, as daungerous upon water as the land ... All the day time the Crocodile keepeth upon the land, but hee passeth the night in the water: and in good regard of the season he doth both the one and the other.

Pliny, Natural history (112 AD), tr. Philemon Holland, 1601. In M. S. Byrne (ed.), The Elizabethan zoo, Nonpareil Books, Boston, 1979, p.116

3.3

Teak zither in the form of crocodile. A Burmese instrument known for over a thousand years.

An Elizabethan text

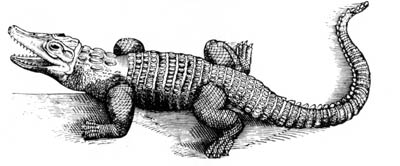

The covering of their backe is distinguished into divers divided shells, standing uppe farre above the flesh, and towardes the sides they are lesse emynent, but on the belly they are more smooth, white, and very penitrable ... The knowledge also of the naturall actions & inclinations of Crocodiles is requisite to be handled in the next place. it is certaine that it liveth in both elements, namely earth & water ... and for the day time it abideth on the land, & in the night in the water, because in the day, the earth is hoter then the water, & in the night, the water warmer then the earth; & while it liveth on the land, it is so delighted with the sun-shine, & Heth therein so immoveable, that a man would take it to he stark dead ... For the flesh of crocodiles, it is also eaten among those people that do not worship it ... Notwithstanding by the Law of God Levit. II. it is accounted an uncleane beast.

Edward Topsell, Historie of foure-footed beastes (1607). In M. Byrne, The Elizabethan zoo, Nonpareil Books, Boston, 1979, pp.116-17, 119

3.5

Shakespeare, who may have seen this representation in Topsell, Historie of foure-footed beastes, made use of the legend of hypocritical 'crocodile tears' which is probably based on Water streaming off the reptile's face when it emerges from the water.

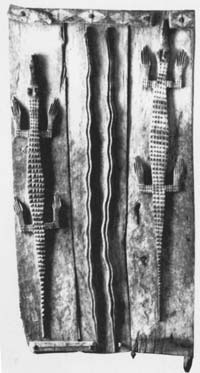

3.4

Crocodiles carved on 3 wooden door by the Bamana people of Africa, where the animals are common along many rivers and often have supernatural associations.

An Enlightenment text

The evening was temperately cool and calm. The crocodiles began to roar and appear in uncommon numbers along the shores and in the river ... The verges and islets of the lagoon were elegantly embellished with flowering plants and shrubs; ... young broods of the painted summer teal, skimming the still surface of the waters, and following the watchful parent unconscious of danger, were frequently surprised by the voracious trout; and he, in turn, as often by the subtle greedy alligator. Behold him rushing forth from the flags and reeds. His enormous body swells. His plaited tail brandished high, floats upon the lake. The waters like a cataract descend from his opening jaws. Clouds of smoke issue from his dilated nostrils. The earth trembles with his thunder.

The alligator when full grown is a very large and terrible creature, and of prodigious strength, activity and swiftness in the water. I have seen them twenty feet in length ... their eyes are small in proportion, and seem sunk deep in the head, by means of the prominency of the brows; the nostrils are large ... so that the head in the water resembles, at a distance, a great chunk of wood floating about.

William Bartram, Travels through North and South Carolina..., James and Johnson, Philadelphia, 1791. In M. Van Doren (ed.), Travels of William Bartram, Dover, 1928, pp.114-15, 122-3

3.6

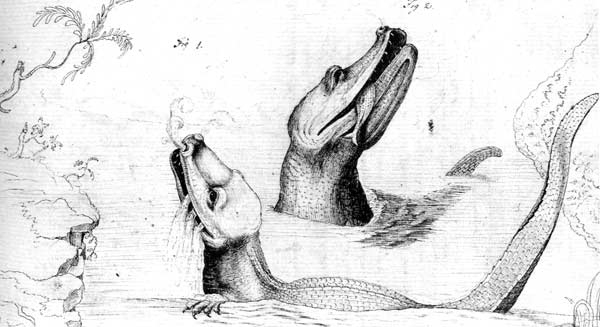

American alligator, from John & William Bartram's America, ed. H. C. Cruickshank, Devin-Adair, New York, 1957 (original held in British Museum, London).

William Bartram's depiction of alligator mississipiensis is both verbally and visually a highly realistic account of the experience of observing the great beast at close quarters in a Florida swamp.

3.7

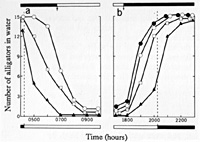

Number of alligators in the water in the morning (a) and evening (b).

In this inscription, Lang renders a complex animal behaviour pattern entirely in numbers.

3.8

Alligator Mississippiensis as depicted in 1976 on the cover of the journal Science.

A Modern Text

Crocodilians utilize both aquatic and terrestrial habitats during a 24-hour cycle. Typically, they spend much of the day on land and are in the water at night. Searching for the basis of this behavior, Cloudsley-Thompson noted a daily rhythm of activity in two captive Nile crocodiles (3). Although he referred to this rhythm of activity as circadian, as yet no evidence has been presented to substantiate the endogenous nature of the response or to identify a periodic environmental factor that might serve as a time cue, or zeitgeber.

Here I present evidence that the amphibious behavior of juvenile alligators is regulated by an internal circadian rhythm, that light is an important zeitgeber, and that an alligator's response to light is adaptable. Although alligators are poikilothermic reptiles, their daily cycle of behavior may be governed proximally by a light-cued circadian rhythm rather than by temperature.

I studied recently captured alligators (Alligator mississippiensis) under semi-natural conditions. Juvenile alligators were caught in Lake Okeechobee and Lake Hicpochee near Moore Haven, Florida, in July 1972 (N = 30), and OctOber 1973 (N = 30). They weighed 0.8 to 3.8 kg, measured 68 to 114 cm in length, and were probably 2 to 4 years old (4). The alligators were marked individually and maintained in two identical outdoor pens ... Air and water temperatures were monitored continuously in one pen. Body temperatures (T,) were taken at varying times of the day (6).

The alligators were observed in the natural light-dark (LD) cycle during July and August 1972, and under natural and experimentally altered LD cycles during October and November 1973. Hourly observations were made between 0400 and 1000 (E.S.T.) and 1700 and 2400 to determine whether individual animals were on land or in the water (7).

In the natural photoperiod, alligators moved out of the water at sunrise and into the water at sunset.

J. W. Lang, 'Amphibious behavior of Alligator mississippiensis: roles of a circadian rhythm and light', Science, vol. 191, no. 4227,1976, pp.575-6