We can summarise the difference between the types of subjects that Yolngu malha speakers and English speakers take for their sentences:

English subjects Matter which is a bounded and spatially separate object and has a specific set of qualities: for example, those which go to make up canoe-ness. |

Yolngu matha subjects A type of relation between named elements of the world: for example, an on-ness associated with beach. |

For an indication of the possible significance of such linguistic differences, we may turn again to Whorf:

The Indo-European languages and many others give great prominence to a type of sentence having two parts, each part built around a class of word-substantives and verbs-which those languages treat differently in grammar ... the contrast has been stated in logic in many different ways: subject and predicate, actor and action, things and relations between things. By these more or less distinct terms we ascribe a semi-fictitious isolation to parts of experience. English terms, like 'sky, hill, swamp,' persuade us to regard some elusive aspect of nature's endless variety as a distinct thing, almost like a table or chair. Thus, English and similar tongues lead us to think of the universe as a collection of rather distinct objects and events corresponding to words... The real question is: What do different languages do, not with these artificially isolated objects but with the flowing face of nature in its motion, color, and changing form; with clouds, beaches, and yonder flight of birds? For, as goes our segmentation of the face of nature, so goes our physics of the Cosmos.

Wharf, 'Languages and logic', in Carroll, pp.240-1

In Yolgnu matha, not only is the 'flowing face of nature' seen in a state of relatedness, but even tables, chairs, and canoes are so pictured. What, then, is the importance of this difference from English? Whorf felt such linguistic variations might ultimately be crucial to the advance of science. He pointed our that the English approach lends itself to classical physics and astronomy, which essentially sees the universe as a collection of detached objects. On the other hand, 20th-century physics with its emphasis on 'the field' and on 'relativity' forms a direct challenge to the ideological underpinnings of English and related languages.

2.2

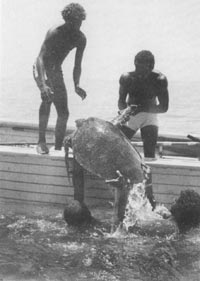

Language is only one of the signing systems being used here. What Sorts of categories might these people have as the subjects of their sentences? Photograph: Oliver Strewe, Wildlight.

Similarly, in modern ecology, relatedness is of the upmost importance. Nature does not draw sharp boundaries around 'swamps' or 'forests', for example. To think of a forest as a separate 'detachable' segment of nature leads politicians to the absurd idea that they can preserve a rainforest by placing a fence around a stand of trees. In an important sense, even a crocodile is not ultimately separable from its environment. If all crocodiles in the Laynhapuy were transported to the Sydney zoo, both the crocodiles and the Laynhapuy would be significantly changed. This is to say that a crocodile in a zoo is not the same creature as a crocodile in the wild. Zoologists who only studied creatures in cages would know very little indeed about their subject.

Ultimately, there is no way of adjudicating which categorisation system is 'more correct' or 'better', though it is possible that particular languages may be better suited to certain specific tasks. Nor can we ever say anything final about how such language categories fit with the 'real' world. As we said earlier, such matters are inscrutable. But as we have also seen, the categories are not ineffable. We can map languages onto each other. The translations may be awkward, but understandings are usually possible based on shared experiences. In other words, we can say something about how categories of one language fit with categories of another, and we can set up criteria for the compatibility of the conceptual systems of languages.

To set up such criteria is beyond the scope of our purposes here, bur it is important to look at some of the issues with which such a discussion must deal. For example, what are the practical, as well as the philosophical implications, of finding conceptual systems that are organised differently, as in the canoe example above? A preliminary answer may be that difficulties of communication between the language groups should be expected, but that these may be overcome with care, mutual respect and attention to detail. Furthermore, such differences of conceptual organisation may help explain differences of belief and behaviour with respect to nature. From what we have seen, and will see below, of Aboriginal attitudes to nature, it is no surprise to find in their language grammatical focus on aspects of relatedness within the natural world.

The study of anthropological linguistics adopts a quite different perspective on the problem from that explored above. Rather than examining grammatical categories, this approach analyses the content of the lexicon (or vocabulary). For example, if we are told that the Inuit (Eskimo) have seventeen words for the one English concept 'snow', does this language difference really matter? This case does not mark a significant conceptual difference: rather it marks an instance of carving up nature with a 'rapier' as opposed to a 'blunt instrument'. The Inuit's fine-grained analysis may be taken as an indicator of special and detailed knowledge of the subject, but it indicates no necessary, or even likely, incompatibility between the two languages.