As well as being title to land the three 'texts' we see in ITEMS 5.8, 5.9 and 5.10 are expressions of Waŋarr (the Dreamtime), so there is a sense in which they are religious icons. They present Waŋarr again to people and thus reconfirm the arrangements whereby certain wäŋa (units of land) are invested in certain groups of people. Wäŋa are symbolised by sacred sites created by the socialising actions of the Makers of Meaning in the world; the people whose land it is are identified in the same symbols.

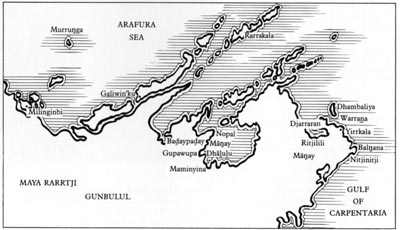

5.11

NE Arnhemland, home of the Merri String.

Names associated with the manikay of ITEM 5.8 shown on a conventional Western map.

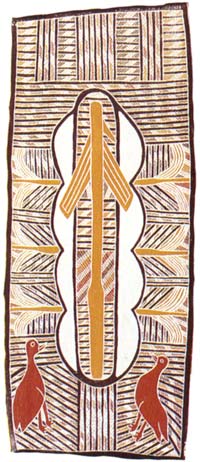

5.10

The sacred walking Stick of the Djan'kawu; moiety - Dhuwa; clan - Rirratjiŋu; painter - Yalmay Yunupiŋu, 1989

ochre on bark, 80 x 30.5 cm.

Wandjuk Marika of the Rirratjiŋu clan told the story depicted in this bark as follows.

This is the special ground, the Bilapinya. You can see two birds, bustards, and one walking stick, Mawalan, which is there. The Djan'kawu put it there and you can see all the trees, whistling tree, she-oak tree. They make this a special area, Bilapinya, and you can see there is a sandhill on top of the painting and on the bottom of the painting, but where the two bustards are standing looking at the ground, Bilapinya, you can see the sign there that's the grass and a little berry, food.

On this painting you can see the walking stick, the special Malawan Stick. On the bottom you can see the flat part for paddling on the sea in the canoe. They used this special Malawan as a paddle for paddling through the ocean to Yalangbara. This is the sacred walking stick I took to the land rights case to explain what the land is. The land is not empty.

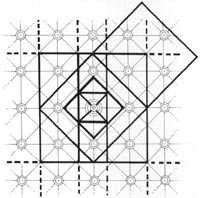

5.12

Grid of songlines from Central Australia.

Peter Sutton suggests that much of the art of the Western Desert Aboriginal people draws from 'a potentially infinite grid of connected places/ Dreamings/ people, in which real spatial relationships are. . . represented by connected roundels' (Peter Sutton (ed.), Dreamings: The art of Aboriginal Australia, Viking, Penguin, Ringwood, Vic., 1988, pp - 84, 85).

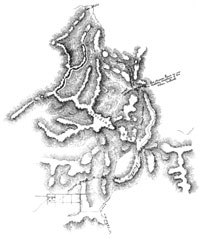

5.15

Map of the beginnings of surveying the Dandenongs, 1859.

5.16

The colony as a grid: Victoria, 1860.

Yolngu collective land ownership is an elusive matter, and being based in metaphor and religion and being characterised by restricted access, the mystery is an integral part of the system. Both the units of land and the corporations associated with them are accomplishments. They are naturalised entities. Part of their functioning is the reification achieved through making the basis of claims the ontological priority of the Dreaming.

5.13

Five Dreamings, painter - Michael Nelson Jakamarra, assisted by Marjorie Napaljarri, Papunya, Central Australia, 1984

acrylic on canvas, 122 x 182 cm.

What the Ancestral Beings did as they journeyed was to bestow names. In the Yolngu world few features of the perceived universe are not named. In bestowing names Ancestral Beings created wäŋa and laid down the relations between them in their journeys. Names are among the most precious items possessed by a clan. Paths were made by walking, or if the journey is by sea they might have paddled in a canoe. A path might be symbolised in other ways, the flight of a mosquito, a bird or a bee, the swimming of a shark or a fish. In social terms a journey links the groups of people in whom the Ancestral beings vested land, and it links them in particular ways. Each landowning group is linked with others by at least one major songline, two such songlines are usual and more than two, frequent. These journeys are routinely re-created in narrative song and dance in the Laynhapuy. The metaphors which form the foundation of the social order are common and everyday knowledge amongst Yolngu.

Ancestors also created the form of the gurruṯu recursion by which all people are connected to each other and to the land. Using gurruṯu and the narrative metaphors, ordered and patterned life is maintained in the Laynhapuy, in the same son of way that it has been maintained for possibly forty thousand years.

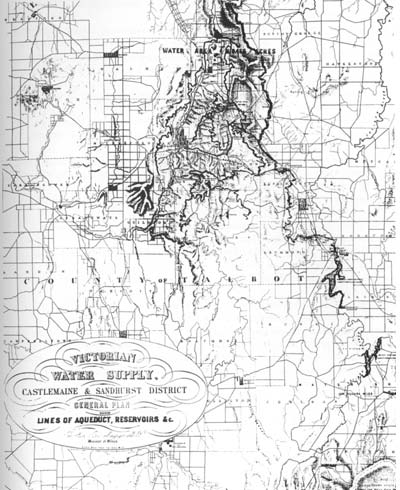

5.14

Grid on landscape: map of Castlemaine water supply, 1867.

FURTHER READING

J. Altman, Hunter-gatherers today: an Aboriginal economy in North Australia, Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies, Canberra, 1987.

J. Bradford, Ancient landscapes, London, 1957. Includes a chapter on Roman centuration.

H. B. Johnson, Order upon the land, Oxford University Press, New York, 1976. An intensive study of the cultural origins and the social, environmental and economic effects of the imposition of rectilinear land planning and usage on vast tracts in the United States.

F. Myers, Pintupi country, Pintupi self: sentiment, place and politics among Western Desert Aborigines, Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies, Canberra, 1986.

G. Presland, The land of the Kulin, McPhee Gribble, Melbourne, 1985. Briefly sets out what is known of the changes in the landscapes of Melbourne over forty thousand years of Aboriginal settlement.

D. W. Thompson, Men and meridians, Canadian Government Publishing Centre, Ottawa, 1972. A study of the history of surveying and mapping in Canada. Provides an interesting comparison with another British colony.

S. Wild, Rom: an Aboriginal ritual of diplomacy, Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies, Canberra, 1986.

N. Williams, Two laws: managing disputes in a contemporary Aboriginal community, Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies, Canberra, 1987.

Nancy Williams, The Yolngu and their land, Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies, Canberra, 1986.

N. Williams & E. Hunn, Resource managers, Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies, Canberra, 1986.

Yothu Yindi, Homeland movement, L38959, Mushroom Records, Australia, 1989.

Yothu Yindu, MainstreamlGuḏurrku, Limited edition K672, Mushroom Records, Australia, 1989. The English language songs on these records were written while Mandawuy Yunupiŋu (formrly Bakamana Yunupiŋu) was working as part of the Ganma Research Group in 1986-88. The Gumatj and Rirratjiŋu songs are parts of song cycles which constitute title to land for the clans. The manikay in ITEM 5.8 would be sung in a similar way.